Polyvagal Theory in Therapy: Understanding and Regulating Your Nervous System

From Lions to Loved Ones: How Our Body Interprets Danger

There’s an old saying among Jews that we don’t name people after the living. The fear, as my grandfather once told me, was that “the angel of death would come down and the dumb SOB might end up confused.”

When I’m explaining our nervous system to clients I tell them something similar. Human beings evolved to respond to very specific, concrete types of danger: lions, tigers, bears, and the like. Fast forward a few hundred thousand years, and your body is still using those same ancient tools as a metric for safety. So when your partner gets mad at you, your nervous system may react as if you’re facing a predator, because the dumb SOB simply doesn’t know the difference.

What is Polyvagal Theory?

Polyvagal theory has become a guiding framework for trauma-informed therapy, mindfulness practices, and somatic healing. Developed by neuroscientist Dr. Stephen Porges, the theory helps us understand how our nervous system constantly scans for cues of safety or danger, and how that shapes our emotions, behaviors, and relationships.

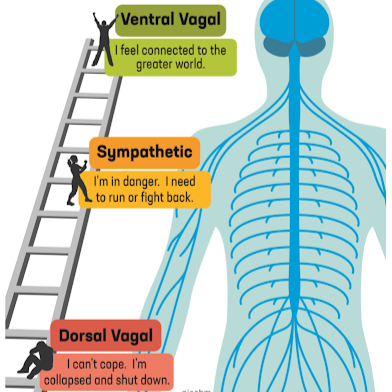

The 3 states of the Polyvagal Ladder

Understanding the three states of the Polyvagal Ladder is essential for anyone exploring emotional regulation, stress responses, or the science behind why we react the way we do. At its core, Polyvagal Theory expands the traditional idea of “fight, flight, or freeze” and explains how our autonomic nervous system shifts between states of safety, activation, or shutdown depending on how our body perceives threat.

Ventral vagal (social engagement system):

This is the top of the ladder. Where we feel safe, connected, grounded, our body is calm and present. When the ventral vagal system is active, we can think clearly, communicate openly and connect with others. This is the optimal state for emotional regulation, problem-solving, and healthy relationships.

Sympathetic activation (Fight or Flight)

In the middle of the ladder is the sympathetic state. When we sense danger, the body mobilizes, heart rate rises, muscles tense, and we prepare to run or fight. This state is not “bad” it’s adaptive but when we live here too often, it fuels anxiety, hypervigilance, irritability, and chronic stress.

Dorsal vagal (shutdown response):

At the bottom of the ladder is the dorsal vagal state, the body’s protective response when a threat feels overwhelming or inescapable. This can look like numbing out, slowing down, disconnecting or collapsing inward. It’s the nervous system’s way of conserving energy and keeping us alive when things feel too much.

These states are not a voluntary choice, they’re automatic, biological survival responses designed to keep us alive. The challenge arises when the nervous system gets stuck, and begins to treat nearly any stressor as danger.

The Only Way Out Is Up: Breaking Nervous System Loops with Polyvagal Theory

According to the Polyvagal Theory, the only way out of shutdown is to move up the ladder through activation. Once we’re in an activated state, we can use regulation tools to calm the nervous system, which then helps us climb to the top of the ladder, the ventral state, where executive functioning and social connection come back online.

Unfortunately, many people get stuck in a single state or trapped in a looping pattern. For example, someone with hypervigilance may live in constant activation until they burn out and drop into shutdown. When their nervous system recovers and comes back online, they move up the ladder into activation only to get stuck there again and eventually fall right back into shutdown. It becomes a never-ending cycle.

The good news is that this pattern can change. Therapy helps you learn to recognize where you are on the ladder, understand what your body is trying to protect you from, and build the regulation skills needed to move toward safety and connection. Over time, the nervous system becomes more flexible and you gain more agency in how you respond to stress.

How Polyvagal Theory Informs Therapy and Emotional Healing

In therapy, Polyvagal-informed work focuses on helping the nervous system find safety again, or for some, safety for the first time. Rather than pushing directly into difficult memories or emotions, we first build regulation and resilience.

This might mean using grounding techniques, mindful breathing, or gentle movement to activate the ventral vagal system. Over time, the body learns that it’s safe to stay present, even while remembering or feeling strong emotions.

Therapists trained in this approach often integrate somatic awareness, noticing sensations, posture, or breath, with traditional talk therapy. By working through the body as well as the mind, clients begin to re-establish a sense of agency and calm.

Polyvagal work also highlights the healing power of connection: safety is co-created through eye contact, tone of voice, and empathic presence. The therapeutic relationship itself becomes a vehicle for regulation.

Applying Polyvagal Theory in Everyday Life

In everyday life, polyvagal awareness helps people recognize and respond to their nervous system states. You might notice when you’re in “fight or flight” mode, when you’re shutting down, or when you’re open and connected. From there, you can gently guide yourself back toward calmness, through breath, movement, self-soothing, or reaching out to someone you trust.

Ultimately, polyvagal theory reminds us that healing doesn’t come from effort alone, but from feeling safe enough to be fully alive. As we learn to listen to the language of the nervous system, we can move from survival to connection and from disconnection to joy.

Take the Next Step Toward Healing

If you’re curious about Polyvagal informed therapy, I invite you to reach out for a consultation. Sometimes, the first step toward getting unstuck is simply allowing yourself to imagine that change is possible.

-Written by Matt Nitzberg