Culturally Responsive ADHD Couples Therapy in NYC: Meaning, Shame, and Repair

What Does It Mean to Be Culturally Responsive to ADHD?

ADHD Couples Therapy in NYC

Being culturally responsive to ADHD means understanding that ADHD doesn’t exist in a vacuum. The way we experience ADHD is shaped by culture, expectations, gender roles, and relationship dynamics. The nature of disability as a cultural construct implies that we might imagine and perhaps create cultures and circumstances in which disability is a non-issue.

This question sits at the center of my work providing ADHD-informed couples therapy in New York City.

My interest in applying Relational Life Therapy (RLT) to ADHD comes from a dialectical tension I see repeatedly in ADHD couples counseling. ADHD symptoms can and do foster anti-relational behavior, yet the way couples attempt to address issues related to ADHD often leaves both partners feeling lonely and inadequate. What does joining through the truth mean when honoring the deficits of one partner may feel like self-abandonment to the other?

Relationships as Culture in Neurodivergent Relationships

Relationships must do the hard work of making their own meaning around ADHD symptoms. Michael Nott, a mentor of mine, once told me that each relationship is its own culture. In this line of thinking, I argue that a relationship should have some measure of sovereignty in how meaning is created particularly in neurodivergent and ADHD-affected relationships.

Terry Real, the founder of Relational Life Therapy writes that “our culture’s norm is to get whatever it is that we get from our partners and then react” (Real, 165). I understand Real’s use of the word react to be deliberate. What we get and what we believe we are getting is socially constructed, interpreted not a priori but within a murky sea of past wounds and present desires.

As Real writes, “behaviors are just raw data… [with] no meaning” (Real, 192) outside of interpretation. Yet it is not only individuals who participate in interpretation. When it comes to meaning, broader culture acts as a ghost in the machine—especially in ADHD relationships.

ADHD, Meaning, and the Feedback Wheel

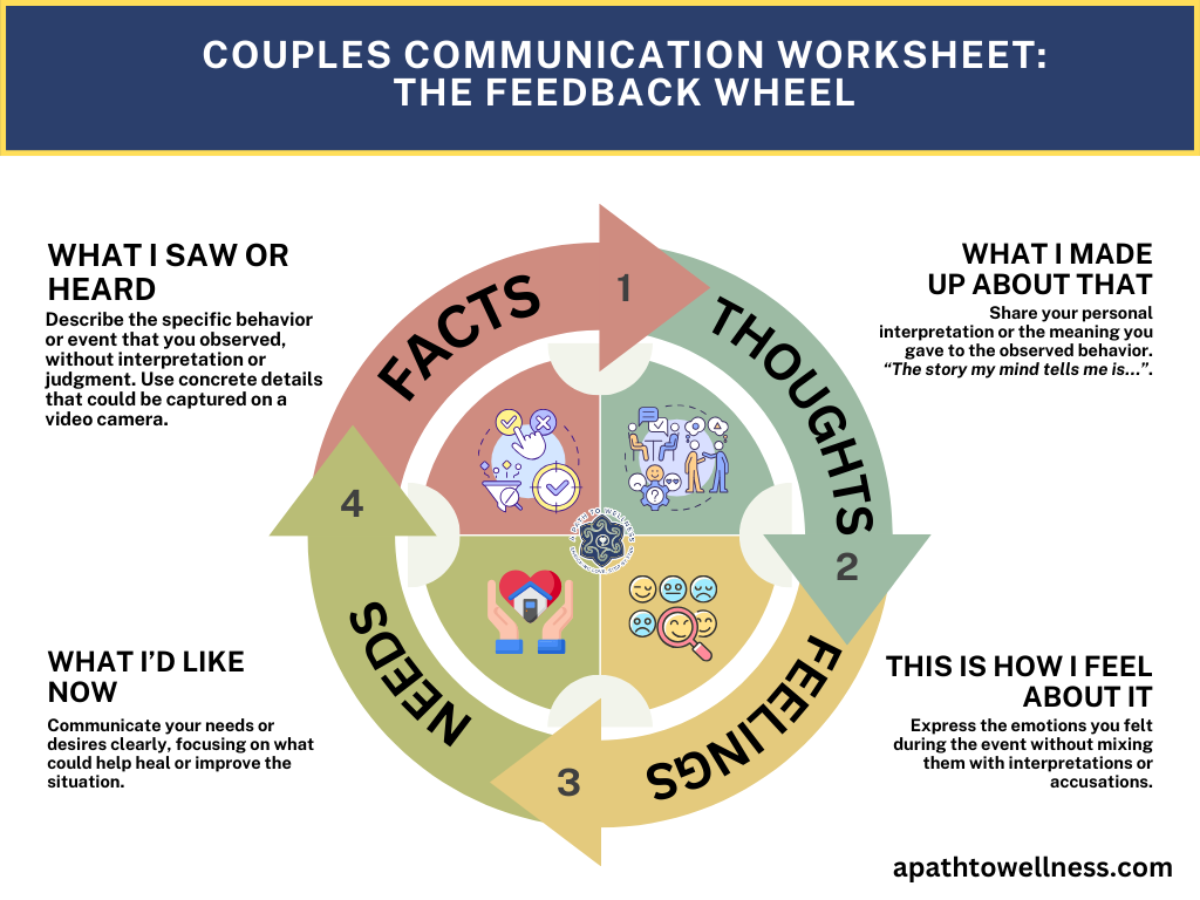

Individuals with ADHD are often told that their struggles with organization, with chores, with lateness are indicative of apathy or lack of care. To narrow in on how this meaning is created, we can use Terry Real’s Feedback Wheel (Real, 189) which explains how the narratives we tell or self, not the behavior itself, creates recurring conflict loops in relationships.

When my inattention is raised, the story I tell myself is that I am inadequate. The story my partner tells herself is that I am uncaring or uninterested which may, in turn, leave her feeling inadequate as well. This recursive process is a common focus in ADHD couples therapy in NYC, where stress and cognitive overload are already high.

Core Negative Images and ADHD Shame

Any conversation around deficits and needs has the potential to activate two Core Negative Images. Relational Life Therapy calls these Core Negative Images the harsh, simplified stories we carry about ourselves and our partners. We can think of this Core Negative Image as a caricature, that caricature may have real teeth for the ADHD partner because it is often grounded in lived reality. If a negative caricature of our partner is enough to trigger us into our Adaptive Child, imagine how triggering a negative caricature of ourselves can be.

For the ADHD partner, these images often hit especially hard because they may be rooted in lived experience. Being seen as “lazy,” “irresponsible,” or “selfish” isn’t just a fear—it’s often something they’ve heard before. If a negative image of our partner can trigger us into defensiveness or withdrawal, imagine how powerful a negative image of ourselves can be.

US Consciousness and Hope

What excites me most about Relational Life Therapy for ADHD couples is its ability to move couples out of blame and into what Real calls US Consciousness.

Instead of “you’re the problem” or “I’m the problem,” the focus becomes: we are caught in something together.

Joining through the truth here must involve the installation of hope, the belief that if we name what feels like a live wire for both partners, something positive can occur.

RLT revolves around empowering both partners to navigate differences; it states that “Interpersonal conflicts are not resolved by eradicating differences, but by learning how to manage them” (Real, 192). ADHD entails greater differences and therefore more work in managing them, particularly in long-term partnerships.

Co-Creating Meaning in ADHD Relationships

In my ADHD couples counseling practice in NYC, I often invite couples to reflect on questions like these:

What meaning have we made about [your partner’s name]’s ADHD symptoms in the past?

What new meanings could we make about those same symptoms going forward?

How can we intentionally create a relationship culture where both of our needs matter?

This work isn’t about pretending ADHD isn’t real. It’s about separating behavior from character and making room for both accountability and compassion.

The Right to Want, Gender, and ADHD

To engage in this work, each couple must take the leap of discussing their own needs and deficits. Real (168) highlights three reasons couples feel uncomfortable asking for what they need:

the potential for rejection or disappointment

the potential for instability

the struggle to feel that one’s needs are legitimate.

Real speaks of the right to want in the context of women’s empowerment, noting that “self-assertion can trigger feelings of shame and guilt” (Real, 169). For women in ADHD-affected relationships, this right to want may be even more foundational.

The mediating effect of ADHD on gender dynamics is well documented. In straight couples, neurotypical female partners of men with ADHD often report compensating for their partners’ symptoms (Zeides & Maeir, 2024). Men partnered with women with ADHD tend to be more critical of ADHD symptoms and less satisfied in the relationship (Wymbs et al., 2020).

Empowerment, Accommodation, and Accountability

Talking about limits and accommodations is vulnerable. Support strategies should not only help the ADHD partner—they should also help the non-ADHD partner get their needs met. As Real puts it: “What do you need from me so that I can help you give me what I want?” (Real, 177).

A key insight from RLT is that empowerment and accountability go hand in hand. As Real notes, “a disempowered partner is seldom generous” (Real, 187). We can extend this further: a disempowered partner with ADHD is also less able to be accountable.

Culturally responsive ADHD couples therapy in NYC doesn’t remove responsibility. It creates the relational conditions where responsibility, repair, and connection become possible.